Biggest risk driver of all is bad governance

Statement by the Secretary-General's Special Representative for Disaster Risk Reduction to the High-Level Politcal Forum on Sustainable Development on Water-related Disaster Risk Reduction under the COVID-19 Pandemic

At the outset, I would like to express my heartfelt condolences to the family and friends of more than 500,000 people who have lost their lives to the COVID-19 pandemic. I also express my condolences to the Japanese people, in particular those who have lost their loved ones as a result of the record-breaking torrential rain in Kyushu this week.

While we are having this discussion, Japan and many other countries are coping with the impact of drought, floods, cyclones and storms while at the same time struggling to contain the COVID-19 pandemic.

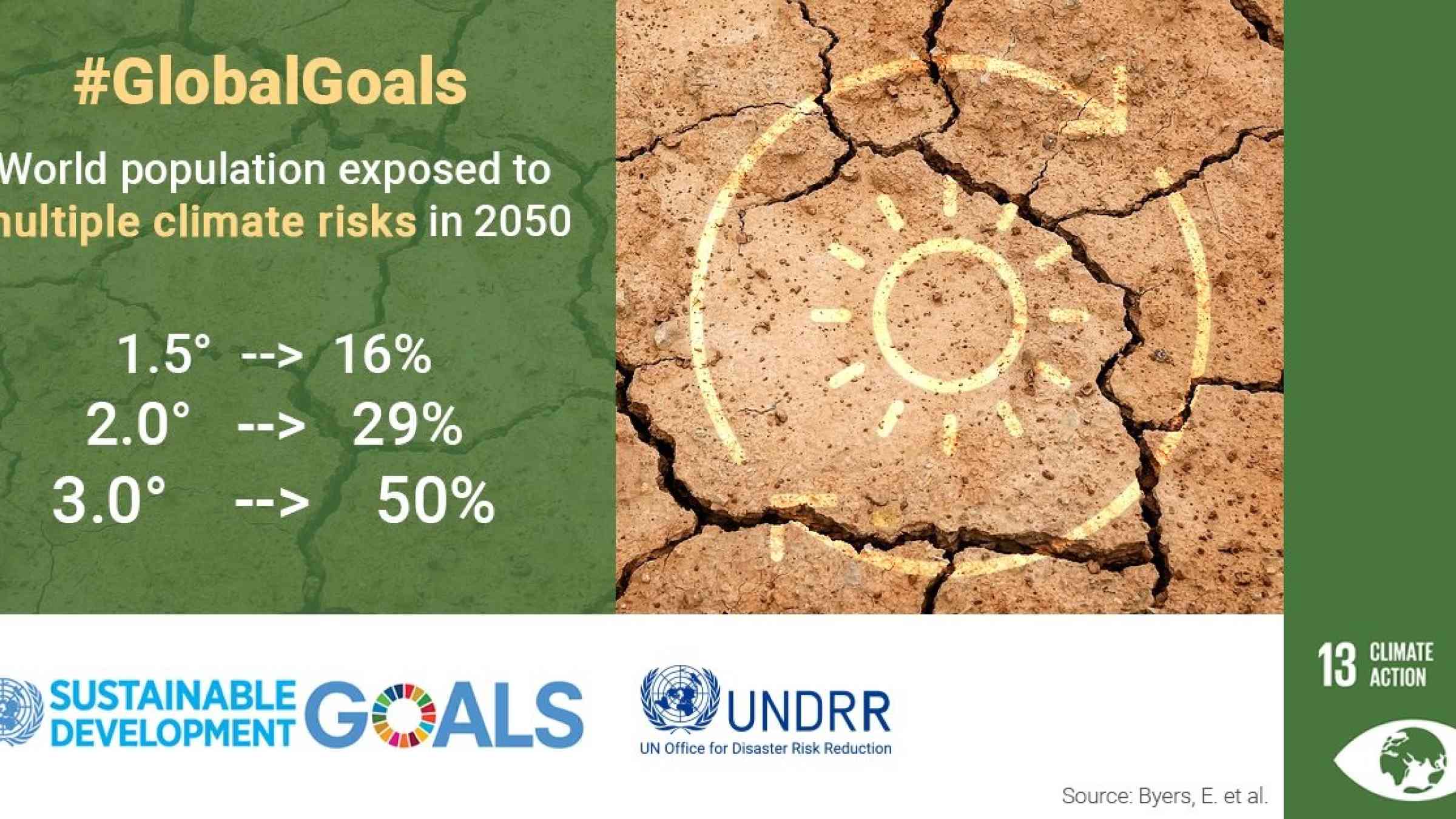

The coincidence of these disaster events across the world is further proof that the era of hazard-by-hazard risk reduction is over.

Disaster management agencies, which previously focused on flood risk during the monsoon season or the threat of a severe storm during a cyclone season, must now move to the stage where we need to manage disaster risk reduction with a multi-hazard approach, and with a clear understanding of the systemic nature of risk.

Failures in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic are evident in the tragic loss of life and health, along with the economic and social hardship of millions of people around the world.

Warnings were largely ignored. The science around pandemic risk was left to gather dust in recent years, and as a result the issue of strengthening disaster risk governance is coming into sharp focus.

Until recent months, it was the general view that more people were affected by floods, storms and drought than any other natural hazard. This is understandable in a world where extreme weather events have risen by over 80% in the last twenty years.

However, already more people have died in the last few months from COVID-19 than have been killed in all the floods and storms of the last twenty years.

When loss of employment and income are factored in, it could well be that more people have been affected by this single disaster than by any other in human history.

The few countries which responded well to COVID-19 were among those who pressed for the inclusion of biological hazards and pandemic preparedness in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction based on their tragic experience of epidemics of Ebola, H1N1, SARS and MERS.

Unfortunately, the review of 81 national strategies for disaster risk reduction carried out by UNDRR, reveals that very few member states have taken full account of the threat posed by biological hazards.

This must and can change. Just as the case of the remarkable progress in many countries to reduce loss of life from hydro-meteorological hazards.

Both Bangladesh and India have strived to maintain a zero-casualty approach to cyclones while putting in place necessary measures to keep millions of evacuees safe from tidal surge, wind, torrential rain and the threat of infection.

COVID-19 has also brought into sharp relief the fact that it is the poor in all countries that suffer the most from disasters.

The most vulnerable living on a minuscule daily wage in slum-like conditions have no access to health care, and are under constant threat of displacement.

National and local strategies for disaster risk reduction which should be in place by the end of this year in accordance with a key target of the Sendai Framework must recognise poverty as a key driver of disaster risk and concentrate on reducing disaster risk for the most vulnerable groups in society.

This is critical if we are to succeed in eradicating poverty and achieving any of the seventeen SDGs.

COVID-19 has also made clear the need to break down silos between disaster risk management authorities and public health management authorities on how governments respond to disaster events.

This includes not only strengthening national health systems but integrating disaster risk management into health care, especially at the local level.

Currently, UNDRR is developing guidance on how to integrate pandemic preparedness into national strategies for disaster risk reduction.

This will help us to better address the question of how countries can meet the challenge of climate and water related disasters while also putting in place measures to prevent, respond to and recover from COVID-19.

COVID-19 has taught us the difficult lesson that the biggest risk driver of all is bad risk governance, and this will be the focus of this year’s International Day for Disaster Risk Reduction on October 13.

I encourage all UN member States, UN agencies and partner organizations to make full use of this year’s International Day to reflect on the issue of governance, to showcase what works well and debate openly the challenges revealed by this pandemic.

Thank you for your attention and for making disaster risk reduction a focus of this year’s High-Level Political Forum.